The central theme in Conan the Barbarian is the Riddle of Steel. At the start of the film, Conan's father tells his son to learn the secret of steel and to trust only it. Initially believing in the power of steel, Thulsa Doom raids Conan's village to steal the Master's sword. Subsequently, the story centers on Conan's quest to recover the weapon in which his father has told him to trust.

Weaponry fetish is a device long established in literature; Carl James Grindley, an assistant professor of English, said ancient works such as Homer's Iliad, the Old English poem Beowulf, and the 14th-century tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight pay detailed attention to the arsenal of their heroes.

Conan's breaking of his father's sword—"[fulfills] a snickering spectrum of Oedipal conjecture" and asserts Homer's view that "the sword does not make the hero, but the hero makes the sword." The film, as Whitlark says, "offers a fantasy of human power raised beyond mortal limits." Passman and other authors agree, stating the film suggests that human will and determination are in a Nietzschean sense stronger than physical might.

SOURCES

Wikipedia

Carl James Grindley "The Hagiography of Steel: The Hero's Weapon and Its Place in Pop Culture" 2004 Source Wikipedia)

Another established literary trope found in the plot of Conan the Barbarian is the concept of death, followed by a journey into the underworld, and rebirth. Donald E. Palumbo, the Language and Humanities Chair at Lorain County Community College, noted that like most other sword-and-sorcery films, Conan used the motif of underground journeys to reinforce the themes of death and rebirth. According to him, the first scene to involve all three is after Conan's liberation: his flight from wild dogs sends him tumbling into a tomb where he finds a sword that lets him cut off his chains and stand with newfound power.

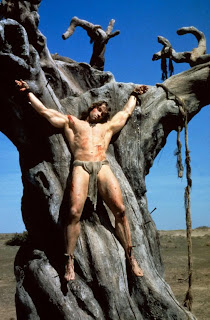

In the later parts of the film, Conan experiences two underground journeys where death abounds: in the bowels of the Tower of Serpents where he has to fight a giant snake and in the depths of the Temple of Set where the cultists feast on human flesh while Doom transforms himself into a large serpent. Whereas Valeria dies and comes back from the dead (albeit briefly), Conan's ordeal from his crucifixion was symbolic. Although the barbarian's crucifixion might evoke Christian imagery, associations of the film with the religion are roundly rejected.

Milius stated his film is full of pagan ideas, a sentiment supported by film critics such as Elley and Jack Kroll. George Aichele, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy and Religion at Adrian College, suggested the filmmaker's intent with the crucifixion scene was pure marketing: to tease the audience with religious connotations. He suggested, however, that Conan's story can be viewed as an analogy of Christ's life and vice versa.

Nigel Andrews, a film critic, saw any connections to Christianity related more to the making of the film. The crucifixion is also reminiscent of Odin being nailed to Yggdrasil or the Titan Prometheus chained to the mountainside of the Caucasus.

No comments:

Post a Comment