Årsgång is the Swedish tradition of a solitary, night-time walk in the forest.

Picture a dark, gloomy forest on a winter’s night, silent aside from the delicate crunch of crisp snow under your feet. Imagine being alone, without technology, far enough from your village that you couldn’t hear a rooster crowing or dog barking. You’ve spent all day in darkness, avoiding eating, drinking, or socializing, and told no one of your plans.

Now it’s midnight, the only things separating you from your objective are the woods and a handful of threatening creatures who want to lead you astray.

That is, according to folklore, how some adventurous Swedes have spent the first moments of a new year.

Participating in the ritual known as årsgång, or “year walk,”, promised information about the future—if a walker followed the rules and reached the local church or graveyard. This form of divination is recorded in documents dating back to the 1600s, according to a chapter by Swedish folklorist Tommy Kuusela in the anthology Folk Belief and Traditions of the Supernatural,* but many such records refer to it as “ancient,” making it unclear exactly when Swedish people began performing the ritual.

A Swedish Christmas Card showing St Lucia in the snow.

Picture a dark, gloomy forest on a winter’s night, silent aside from the delicate crunch of crisp snow under your feet. Imagine being alone, without technology, far enough from your village that you couldn’t hear a rooster crowing or dog barking. You’ve spent all day in darkness, avoiding eating, drinking, or socializing, and told no one of your plans.

Now it’s midnight, the only things separating you from your objective are the woods and a handful of threatening creatures who want to lead you astray.

Årsgång is far from the only form of supernatural divination in Swedish folklore, but it is one of the more extensive. While rituals like circling the house three times counterclockwise with a porridge scepter before eating Christmas dinner were supposed to provide a limited glimpse of things to come, the year walker had the potential to learn not only his own fate but that of the entire village.

With greater reward, however, came greater risk.

The walk took place on New Year’s Eve or another winter holiday, when Europeans believed dark forces and supernatural beings were active and the dead mingled with the living. This let the walker tap into the prophetic power of the season, but it also meant opening oneself up to frightening encounters.

Cemeteries were particularly active. Walkers reported songs coming from open graves, dead spirits walking about, and fresh graves that did not exist before, according to Kuusela.

They could also expect to encounter frightening entities like the brook-horse (bäckahäst) and the huldra, as described in an account of årsgång added to the University of Southern California’s Digital Folklore Archives by student Cameron Steurer.

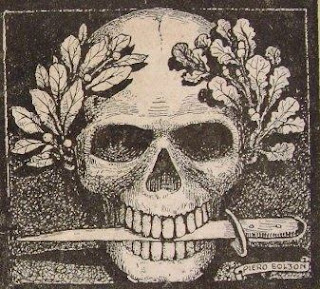

A brook-horse, from Swedish folklore.

The brook-horse, she learned from a Swedish friend, would invite children to ride on it and lengthen its back to accommodate more and more children. “When the horse felt it had enough riders, it would jump into a body of water, drowning all of its riders and taking their souls for its own,” wrote Steurer.

The huldra, on the other hand, was a beautiful, tree-like nymph. “Said to be the forest guardians, they would lure people to their homes to either marry them or kill them,” Steurer wrote. “Either way, the victim would be lost forever.”

Other creatures did all they could to distract a year walker. Talking, laughing, or being afraid was forbidden during the somber walk, and those who broke these rules sometimes sacrificed their sanity, lost an eye, had their heads distorted, or simply disappeared, according to 18th-century records of failed walks translated into English by Kuusela.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE HERE